Living Reviews: The Wikipedia of Science

How journal papers that can be constantly updated allow researchers to better tell the never-ending story of science.

by Miriam Frankel

August 29, 2025

Wikipedia is one of the Internet's greatest success stories. The non-profit, online compilation of human knowledge has grown mind-bogglingly fast since its launch as a passion project in 2001, and is now kept up-to-date by an army of volunteer editors. Today, it is one of the most visited websites in the world, and—despite its faults—it has essentially replaced traditional sources of knowledge, such as encyclopaedias. The English version alone has over seven million entries.

But the idea at the heart of the project—that an article can be a living entry and evolve to remain relevant over time through successive updates—had already occurred to the physicist Bernard Schutz, now at Cardiff University, in the UK, back in the 1990s, as the Internet gained traction.

"It seemed obvious to me that if you're not physically printing an article, then why not take advantage of the fact that you can update it?" Schutz says.

In 1998, three years before Wikipedia came online, Schutz

launched the online scientific journal

Living Reviews in Relativity, which is

has been dubbed the "Wikipedia of science" (or, at least, of the physics sub-discipline of relativity). Schutz was the founding director of the Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics (Albert Einstein Institute) in Potsdam, Germany, at the time, and that institute published the journal until 2015. The journal is now hosted by Springer Nature and publishes articles that are free to read, contain various multimedia elements, and can be updated any time—much like a Wikipedia article. The difference is that the journal articles are peer-reviewed by subject experts, and the articles' authors (who are themselves experts selected by a team of editors) are the only people allowed to make or approve updates. (By contrast, anyone can edit most Wikipedia articles.)

If you're not physically printing an article, then why not take advantage of the fact that you can update it?

- Bernard Schutz

When Schutz set up

Living Reviews in Relativity, the field of general relativity—Einstein's theory of gravity—which had long been fairly small, started to expand rapidly. This was partly down to gravitational wave detectors being built and black holes and other objects described by general relativity becoming central to astronomy. Schutz thus initially conceived of the journal as an effective way for new research students to get up to speed, rather than as a means of disrupting the

traditional science-publishing model.

"There wasn't a review literature for general relativity that was at all comprehensive, so we thought we're filling a gap for our subject," explains Schutz. "We didn't really think we were being pioneers."

Most open-access journals are financed through article processing charges, which are paid for by the authors or their institutions. But Schutz didn't think that would work for review articles, which are larger in scope and tend to be a lot more time consuming to write than normal papers. In fact, living review articles can be over 100 pages long, more than ten times the length of a standard research paper.

"If you invite somebody to write a review, it's a lot of work, so it's hard to ask them to pay an article charge," says Schutz. "So we thought, let's not charge the author, let's not charge the reader and let's just take on the overhead cost of running the journal through the Max Planck Institute."

Researchers in the field were enthusiastic about the project from the get-go. "It was surprising to me how big the reception was, how welcoming people were," Schutz recalls. "We formed a very good editorial board."

That said, there were some early philosophical challenges. In particular, the board had to decide whether each update would count as a whole new article. "We struggled for a while with 'what is an article?'—if an article is updated, is that the same article or not? That's important for citation counting and things like that," explains Schutz. "We finally adopted the policy that every update is technically a new article and the old article is still available on the website."

Shaking Up Science Journals

Editor-in-chief of the biomedical journal eLife, Tim Behrens, on experiments with post-publication peer review.

Full Podcast

A couple of other directors at the Max Planck Institute eventually followed suit, with the journal developing into a series, including

Living Reviews in Solar Physics and

Living Reviews in Computational Astrophysics. "Many of the reviews are the standard reference in that sub-field," says FQxI's

Don Marolf, a physicist from the University of California, Santa Barbara, who currently sits on the journal's editorial board.

It's easy to see why: Reviews, particularly up-to-date ones, help research students learn about their subject areas. They also catalyze innovation by connecting to, and taking inspiration from, research in different fields. "As someone who is quite broad in my interests, I sometimes get into a new field and the first thing I do is look at the best, most recent review in that area," says FQxI's

Hiranya Peiris, a physicist at the University of Cambridge in the UK, who also a member of the editorial board of

Living Reviews in Relativity.

By 2015, the journal series had found huge success:

Living Reviews in Relativity was one of the most highly-cited open-access journals in the world. However, Schutz was retiring from his role at Max Planck, and the series was sold to the mega academic publisher Springer (which has since morphed into the even more sprawling Springer Nature publishing house)—something he had major qualms about. "I'm concerned about the way scientific publishing is driven by a small number of commercial publishers to make big profits," Schutz says. "That doesn't help the science at all."

Many of the reviews are the standard reference in that sub-field.

- Don Marolf

In this case, however, Schutz believes the move worked out well. "Springer knew they were taking on something that would lose money and we insisted that if they took it over, it would remain open access," he says. The commercial publishing house has honored that agreement for the past decade by pairing it with a commercial sister journal in relativity, whose editorial staff supports both journals.

Monopolization by a small number of science publishers remains a valid concern, as does an additional worry that such models give too much gatekeeping power to a handful of academics. The journal's editors are aware of fears about a few individuals "owning a space" and becoming anointed as authorities in the area for extended periods of time, at the expense of other emerging experts, says Marolf. They take pains to avoid this perception, he adds: "Sometimes we will intentionally choose authors with different viewpoints and ask them to work together—such 'adversarial collaborations' can result in "very nice reviews."

There are other challenges with the day-to-day running of a living review. The task of producing a 100-page review and maintaining its relevance for years to come can be perceived as onerous—and it's not always easy to commission and maintain. "The challenge is getting people to write them when you need them because it is a large commitment," says Marolf. "Not only are you going to write it now, but you're going to come back in a few years and update it."

The reviews are also a strain on editors because they must often chase frequent updates. "There are articles which I think are on great topics that have not been updated in forever," says Peiris. "It's incredibly challenging to keep them updated to the level that people anticipate."

Given how long the articles are and the large amount of work that goes into keeping them up-to-date, they aren't published in huge quantities—typically well below 10 reviews per year. But when it all comes together, researchers ultimately see it as a "a huge honor" to have written a living review, says Peiris. Schutz highlights the chance for the author to make their work relevant for long periods of time as another benefit for authors, adding encouragingly that "the update is not nearly as much work as the original review."

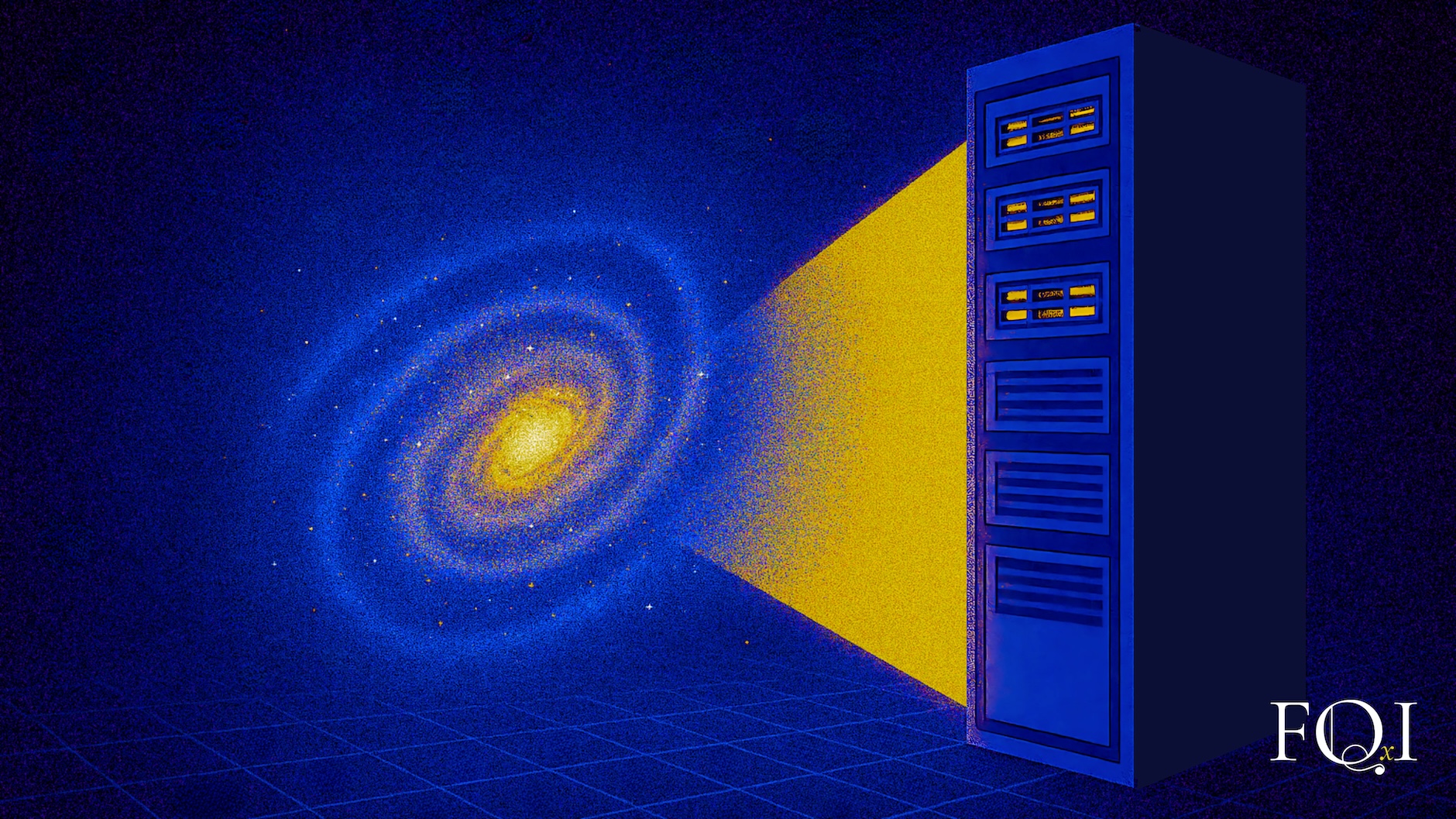

Numerical relativity in cosmologyComplex supercomputer calculations could help cosmologists understand what happened before the big bang, and more.Credit: Gabriel Fitzpatrick for FQxI, © FQxI (2025)

Numerical relativity in cosmologyComplex supercomputer calculations could help cosmologists understand what happened before the big bang, and more.Credit: Gabriel Fitzpatrick for FQxI, © FQxI (2025)The editors also feel an immense sense of pride on publication, alongside the authors, having invested much more time in the paper than editors at a standard journal. "I recently, commissioned an article on numerical relativity in cosmology, which has

just been published, and that was a process which took over a year," Peiris says. "So far, it's been a very positive experience because you do get to shepherd an article through and contribute your intellectual effort."

One of the authors of that review, which discusses recent advances in the use of high-powered computing to analyze cosmic data, was Eugene Lim, at King's College London, UK. He had approached the journal with the idea, based on a talk he had given at a conference a few years ago. The choice of journal was "obvious" to him. "Some of my favorite reviews were living reviews," he says. "It's especially great for a topic like numerical relativity in cosmology where things are just constantly happening because it is starting to become trendy."

While the clear benefit of living reviews is that they can be constantly updated, the downside is...that living reviews can be constantly updated. Is there added pressure on authors and editors knowing that they have embarked on a potentially never-ending story?

It's been a very positive experience because you do get to shepherd an article through and contribute your intellectual effort.

- Hiranya Peiris

Lim admits it was hard to find the time for writing the review in the first place, among the many other commitments required of academics (including doing original research, teaching classes and mentoring students, and administrative responsibilities). Lim and his colleagues are now committed to updating the review going forward. "We already started the document where we are putting in stuff that we want for the next iteration," he says.

But every single update also has to be peer reviewed. "I was involved in a case where one reviewer said 'that's great' and the other sent lots of pages of extra references, saying the authors had missed an entire new topic," says Peiris. "So the authors are going back to the drawing board on that one."

If the original authors are not able to make updates, then co-authors can sometimes be added to the papers, with the permission of the original authors, says Marolf.

This begs the question: how long can a review keep being updated? It seems that till death do reviews part. "You definitely can't update a review after the authors have died," explains Peiris. "There was actually a case of this recently and after a long debate we decided to not update that review—I don't think it is necessarily ethical to do that." In that case, the editors can instead commission a new review, to be written from scratch, in the same field.

The fact that living reviews don't actually make any money means the innovative model is still rare in the world of scientific publishing. "I think some journals have started up and then fallen by the wayside," says Schutz. "The model is not commercial, so it requires you to put in resources."

Nevertheless, a lack of profit hasn't held back Wikipedia, which generates much of its income from donations. "What I would like to see is more scientific institutions taking responsibility for their publishing, as we did," says Schutz, although he acknowledges that this may be difficult in the current funding landscape. Peiris argues that professional societies, such as the Institute of Physics, in the UK, should get involved financially.

The Problems with Peer Review

Ivan Oransky of Retraction Watch and arXiv discusses whether science publishing is broken.

Full Podcast

There have been a few success stories, however. In 2007, Robert Kuchta, a professor of biochemistry at the University of Colorado Boulder, in the US, suggested a similar approach for the journal

Chemical Reviews, where he was then an associate editor. "I brought up the idea at one of the editorial advisory board meetings and then it was adopted right away," he recalls.

Kuchta was concerned with the need to "minimize labour," he explains. "Writing a review article

de novo is a huge undertaking, however, when you are just updating it, it might be five percent of the work."

The main challenge for

Chemical Reviews has been getting enough people to contribute reviews and updates on all the subject areas that need covering. This may be a particular issue when the journal is covering a very large discipline, he notes. Both Kuchta and Schutz would like to see more journals adopting the model. "It's especially needed in the biological sciences because they just change so quickly," Kuchta says.

But other journals may be put off from using the living-reviews model by the fact that the publishing landscape has changed significantly since 1998, when

Living Reviews in Relativity was launched, or even since the revamp of

Chemical Reviews a decade later. How can living reviews best thrive and improve going forward, particularly at a time when large language models such as ChatGPT and Claude can easily write research summaries?

Schutz argues that AI could become useful in the future. But, he argues, the current crop of AI models simply isn't reliable enough to replace human-produced living reviews. If used, AI must not be regarded as "authors," but instead should be used as "tools" under human supervision to catch mistakes in papers.

What I would like to see is more scientific institutions taking responsibility for their publishing, as we did.

- Bernard Schutz

In an ideal future, one could imagine that AI would be free from the individualistic perspective of a certain researcher, offering benefits over human authors, in that regard, says Schutz; but we are far from that scenario. As it stands, an AI's knowledge and expertise is only as good as the data it is trained on. "There's a very strong trend in the research literature of sidelining work by female first authors or authors from developing countries or smaller institutions," Peiris says, noting AI is already known to amplify such biases. What's more, peer review is an essential part of living reviews. "It's a collaborative enterprise that I don't think can be outsourced to an AI," she adds.

Marolf is also sceptical. "Whenever I've attempted to play with getting AI to summarize technical things on the web for me, it's a disaster," he notes. Given the widely-reported problems with AI hallucinations (reporting false answers with high confidence), Marolf argues that updated reviews should be used as benchmarks against which such AI summaries can be compared. "If anything, AI has just added to the confusion and increased the need for reliable sources of reviews," he says.

But there may be a better source of inspiration for improving living reviews than AI— one that now seems quaintly old-fashioned. "I think the difficulty we found is that some reviews are very, very long," says Schutz. "Perhaps they'd do better if the articles could be broken down into smaller subjects, potentially getting different people collaborating on different sections of the review."

Sound familiar? This is reminiscent of Wikipedia's open collaboration model for writing and editing.

"We should totally have a team of authors who writes the original review based on the Wikipedia model," says Kuchta. "I wish I'd thought of this before."

Perhaps then, living reviews will truly become the Wikipedias of science.

Lead image credit: NASA, ESA, Joseph Olmsted (STScI). Artist's impression of a pair of active black holes at the heart of two merging galaxies.