By some reports (speakers of Russian correct me here) a passable translation of "Sputnik" is "co-traveler," in the sense of "one who travels alongside." There's a whole art to scientific designation -- the choosing of terms for what we create, or discover -- but that old familiar name seems doubly apt. In one sense it's appropriate for the basketball-sized piece of machinery that became the first, fifty years ago, to travel alongside the earth; in another, for the meaning it holds today.

image:Dan Mogford

In an age when the thermosphere is crowded with weather and communication relays, space shuttles, even mechanical detritus, it's worth taking a moment to reflect on what Sputnik really was: the first artificial satellite.

Though of course it was also much more. For one thing, it was terror.

"Somewhere over our heads, beeping triumphantly, was an electronic ball which had been launched and constructed behind the Iron Curtain," recounts Stephen King in his semi-autobiographical *Danse Macabre.* He's reliving the moment when the manager of the movie theatre where he sat as a child watching *Earth Versus the Flying Saucers* stopped the show to inform the assembled audience of popcorn-throwing adolescents that, horror of horrors, the bad guys had beaten us into space. "The manager stood there for a moment longer, looking out at us as if he wished he had something else to say but could not think what it might be . . ."

The master of so many of our nightmares (I still dream about the Overlook Hotel on occasion, and I read that book when I was nine) was himself initiated into anxiety by the stepping of Mother Russia into orbit. No wonder; Sputnik was ostensibly a scientific enterprise, but its larger mission -- one it accomplished with grim effectiveness -- was to show the U.S. how easily the U.S.S.R. could overfly our land. Lookee here, Sputnik announced to every backyard radio operator tuned in to its 40 MHz beep, let's just say the next one is carrying a hydrogen bomb. What's to stop us from dropping it on your city? Or yours? Or yours . . . ?

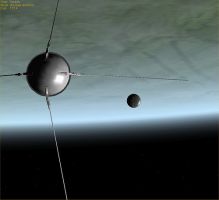

image:FlyingSinger

That was then. The flying saucers never showed up (though we're working on it); eternal enemies are now, if not exactly chummy, at least no longer sworn opponents in a tug-of-war game with the world. The global thermonuclear exchange I grew up fearing, in which the U.S. and Soviet Union would sterilize the planet's surface and, for all we know, end life in the universe, never occurred; that "choice of nightmares," (to borrow Conrad's phrase) is over. To be sure, paramount among our concerns is still the nuclear device, this time made small enough to fit inside one of those suitcases waiting quietly by the check-in line at Grand Central Station. We have our own nightmares -- but Sputnik is not among them.

The Space Race, that is, did not lead to destruction: it led to discovery. Steve Garber, NASA History Web Curator, puts it bluntly: "The Sputnik launch also led directly to the creation of National Aeronautics and Space Administration." If not for Sputnik, would we have been motivated enough to create Explorer I, and discover the magnetic belts that wrap our planet? Without the unfortunate dog Laika, the first mammal to rise into orbit, would we have sent mammals named Bowman and Lovell around the moon in '68? Would we have sent others to walk on it in '69? Would we have built the Hubble? The ISS? Really?

The space race is ended now, but the promise it initiated remains. And significantly, it is now an international promise. The Chinese are targeting a moon landing within a decade, and looking at their own habitable satellite. The first Malaysian astronaut will be teaming up with a Russian cosmonaut and an American astronaut soon (the first female commander of the ISS) -- onboard the International Space Station. If we in the U.S. ever get our financial house in order, there is still that moon/Mars initiative sitting on the table somewhere at NASA (President Bush may not have mentioned it since the unveiling, and people I speak with at NASA have grave reservations, but that's another story). Our future in the sky is sketchy, but with distinct patches of illumination.

So here's to the beeping, sky-crossing pioneer -- and here's to a reconsideration of its meaning. Where novel technology once horrified us, it has ultimately united us in common purpose. Science can still bring us together, perhaps most especially where other cultural systems fail, in an international spirit of discovery.

For all humanity's rough edges, exploring the universe is what we do. We are all co-travelers.