image: Royalty-free image collection

Connecting to our ongoing discussion in these pages over the likelihood that we will be able to recognize alien life, the multiplicity of possible forms life probably takes, and the difficulties of knowing how to scan for intelligent species, here's some excellent late-summer reading: an article called Could alien life exist in the form of DNA-shaped dust? at Newscientist.com:

"According to a new simulation, electrically charged dust can organise itself into DNA-like double helixes that behave in many ways like living organisms, reproducing and passing on information to one another.

'This came as a bit of a surprise to us,' says Gregor Morfill of the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics in Garching, Germany. He and colleagues have built a computer simulation to model what happens to dust immersed in an ionised gas, or plasma.

The dust grains pick up a negative charge by absorbing electrons from the plasma and then this charged 'nucleus' attracts positive ions, which form a shell around it.

It was already known that this system can produce regular arrays of dust called plasma crystals, and some experiments have also shown hints of spiral structures. Now, Morfill's simulation suggests that the dust should sometimes form double helixes."

image: ninjapoodles

Double helixes? Radar go up at this point, and they should. As the article goes on to note, these helical structures contain information in the form of two "stable states," (an arrangement that allows for binary encoding?). A series of sections composed of chains of these states can be broken off and copied. The spirals, all of whose actions are driven by plasma, compete in that sense for energy resources, with the winner producing more copies of its replicating information-sequence than the loser.

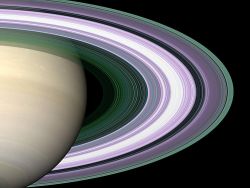

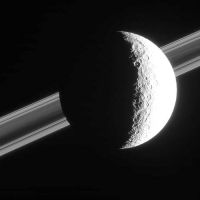

Sound like natural selection? So far these spirals exist only in simulated form (but do simulations enjoy an ontology of their own?), but there may be instances of just such crystals in our neighborhood: say, Uranus' or Saturn's rings. The ice crystals there, blown about by the solar wind via the planet's magnetic fields, constitute another dust-in-plasma combination, and might just fall naturally into alignments like the ones seen in Morfill's simulation.

Is it possible, then, that within the ice rings surrounding Saturn or Uranus is a form of slowly evolving life? No one is betting on it, but the speculation itself is important. For one thing, it's right in the middle of Foundational issues. Before we can ask whether we are the only ones living in the Milky Way, we need to know: what makes something alive? Morfill's simulation is not a living thing, and it is not a simulation of a living thing; but it looks eerily like the latter. If we are to agree that self-replicating double-helixes that (may) undergo selective adaptation in the competition for energy within planetary rings really have nothing to do with the appearance of life a few thousand miles down on planetary surfaces, we have to accept some arbitrary seeming coincidences. On the other hand, if there is a deep connection here, is it telling us that life is simply a matter of a particular configuration -- one that can be summoned up, literally, in whirling dust?

At some point in human history, it seems, we must have resembled Morfill's plasma spirals. We know there was a time when the DNA, predecessor RNA or some chemical underpinning existed as a self-replicating structure that nevertheless would not pass the test for any reasonable definition of life. (Clay or ice crystals are a favored example among biologists.) But when do these structures become something else -- when do they become part of the biotic, instead of the abiotic, landscape? Morfill's work suggests that in scanning the heavens for our neighbors we may have to include far more unlikely searches than we had imagined. After all, maybe the icy surface of some distant moon itself will be watching us.

image: kokoglak