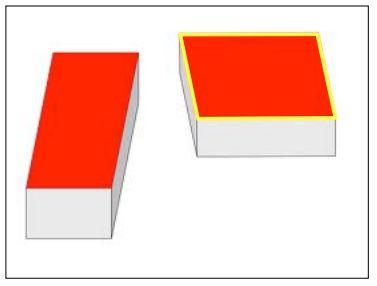

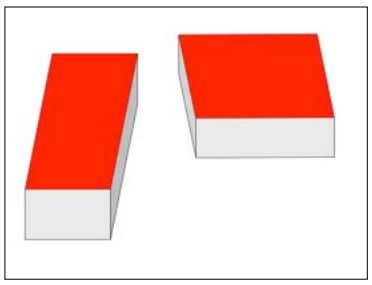

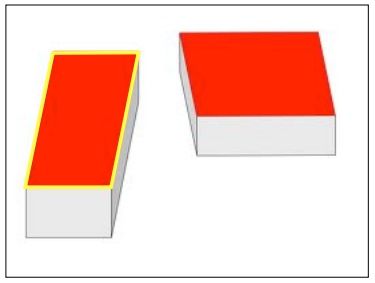

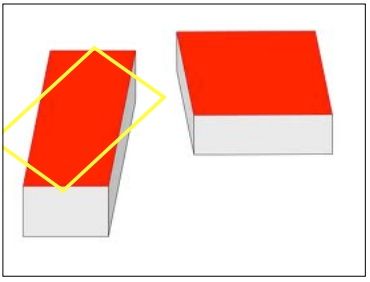

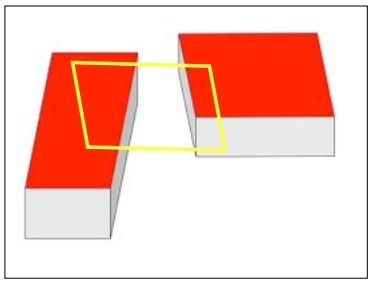

To set up this post, which covers the "Memory" session of the FQXi meeting from Bergen to Copenhagen (I'm still playing catch-up on covering the sessions), take a look at the image to the right, courtesy of psychologist Henry Roediger. Both red-shaded rectangles are the same size, but we think they are not. (If you don't believe me, Roediger created a series of images, trailing down the page, to convince you.) The illusion is meant to highlight how easily our brains can be fooled -- and why false memories are so easy to implant. But more on that in a minute.

I found the psychology talks in the Memory session particularly fascinating, although I guess that a lot what they had to say is old news (in some cases very old news going back to the 70s) to people more familiar will their fields. However, their talks created a lot of excitement amongst the physicist-heavy audience who hadn't met them before and appreciated the slightly different questions they were asking about the nature of time in psychology. I've already mentioned that Kathleen McDermott spoke about "mental time travel" and the idea that imagining the future (a process she termed "pre-experiencing," which apparently humans do every 16 minutes or so) and remembering the past are intimately related in the brain, and are highlighted in similar ways in fMRI. As some had commented on my earlier post, it's perhaps not _that_ surprising, given that when we think about what might happen, we have to construct a picture based on events from our past. Nonetheless it was interesting to hear about the history of the development of these ideas (and you can view her slides here).

The term "mental time travel" was coined by psychologist and neuroscientist Endel Tulvig. In the 1980s, he studied the case of a man, dubbed K.C., with global amnesia, who like the protagonist of the movie Memento, could not remember anything from more than a few minutes before. When Tulvig pushed KC to try and think about what he might do tomorrow, he replied that he did not know, and when he tried to think about it, he experienced only a feeling of "a big blankness sort of thing," or a feeling of "being in a room with nothing there and having a guy tell you to go and find a chair, and there's nothing there" and that this was the "same kind of blankness' he felt when he tried to think about what happened yesterday.

To see if the two processes are underlain by the same core cognitive capacity, McDermott used fMRI to scan 21 healthy young adults while they thought about a memory from their past (for example, getting lost), an imagined event involving themselves in the future (for example, going to the library) or an imagined event happening to someone else, at no particular time (the example McDermott used that apparently worked particularly well was "something involving former President Bill Clinton" -- provoking some giggling around the room). She noted that although subjectively we each know when we are thinking about the past and the future and can differentiate the two, the brain activity associated with the two was surprisingly similar.

McDermott's next question was: "Is there anything special about time?" Further tests on 27 healthy young adults suggested no. In this set of experiments, McDermott and colleagues compared scans while people were remembering a specific memory in a familiar context, envisioning a future memory within familiar context, and envisioning a specific future episode occurring in an unfamiliar context (for instance, at a bullring). In this case, the scans for both past and future were similar if the context was familiar, but not if the future episode was imagined to be occurring in an unfamiliar setting. So it was not the time difference that caused a difference in brain activity, but the spatial difference. It was a new psychological take on the old physics' question of which is more fundamental: time or space?

(Edited on 14 Sep 2011 to add, thanks to Ian's comment below:) One of the best questions of the session was posed by Simon Saunders' young son Ari, who asked if KC and others with global amnesia can dream, given that dreams involve memories. The answer is that nobody knows, but it's something they'd like to look into.

McDermott then touched on the idea that past "memories" are constructed just as future imaginings are, which ran nicely into Roediger's talk on false memories that I mentioned at the start of this post. Roediger's point was not just that it is easy to misremember the past, but that people can be extremely confident about their errors. He gave an example of how poor people typically are at assessing the uncertainties in their answers: "Ask US students what the capital of Australia is and most will say Sydney and will rate their answer with high confidence -- 3 or 4 on a confidence scale of 1-4!"

[youtube: 7bs5yMU-0FM, 560, 340]

At his memory lab at Washington University, Roediger and others (including McDermott) were able to create false memories in the lab, and then compare the confidence levels of those reporting the memories with the actual accuracy of their answers. For instance he presented participants with a list of words (bed, rest, awake, tired, dream, wake, snooze, blanket, doze, slumber, snore, nap, peace, yawn, drowsy) that were all related to another word -- sleep -- which was left off the list. Participants were fooled into thinking that the word "sleep" had appeared on the list, with high confidence, when it had not. Though that's a highly controlled example, unfortunately the same principles lie behind false eye-witness testimony. "Police line-ups are like a multiple choice exam, where people often just go for the closest match," said Roediger. "But it's not emphasized enough that "none of the above" is an acceptable answer."

(All images courtesy of Henry Roediger.)