As physicists wrangle over whether string theory truly represents reality, FQXi invited Moataz Emam of Clark University to ponder over the fate of string theorists like himself, if string theory turns out to be wrong.

--

From Moataz Emam:

As a string theorist, I am often asked an uncomfortable question: "What will you do if someone proves that subatomic particles cannot possibly be made of strings?"

What will happen to my career and life's work if string theory is falsified? Is it worth the risk? These are certainly valid questions. My answer is that even if string theory is proved "wrong," it will still survive, and possibly break away from mathematics and physics to form a new and separate academic discipline. Bear with me.

String theory already occupies a special niche in the history of science. It's our best bet for finding a theory of quantum gravity, as FQXi's Renata Kallosh of Stanford University explains in this article connecting string theory with cosmology , as well as for finding a theory of everything. However, it is also the only theory of physics with no experimental backing that has managed to not only survive, but also become "the only game in town" (to quote Nobel Laureate Sheldon Glashow).

This lack of experimental support has been seized upon by string theory's vocal critics, notably FQXi's Lee Smolin, of the Perimeter Institute, and Columbia University's Peter Woit. In his book, "The Trouble with Physics," Smolin points out that this "faith" in the string hypothesis has affected funding and hiring policies in a negative way, boosting the theory's prominence disproportionately compared to other approaches to quantum gravity. Although there are many counterarguments to be made, it seems that string theory does receive more hype than it deserves if evaluated solely on its applicability to nature.

(Image: Lshift)

In fact, string theory has so far failed to conform to the falsifiability criterion laid down for a scientific theory by Karl Popper. It might be argued that this situation is temporary--eventually technology will catch up with string theory. This hope is what saves string theory from being little better than astrology or creationism.

But back to the original question: What if it turns out that string theory does not describe nature? Will I, and other string theorists, be out of a job? My answer is no, and here's why.

String theory has provided us with a wealth of possible solutions for the state of the universe that arise when we try to reduce the ten-dimensional string theory to the four spacetime dimensions we are familiar with. We have such a plethora of outcomes that they collectively form a "string theory landscape" of different theoretical descriptions of possible universes. The lack of experimental results to guide us through the vast string landscape leaves string theorists with no choice but to systematically explore all of it!

These explorations, even within theories that we already know are not related to nature, have resulted in the discovery of deep and elegant mathematics. Mathematicians today work in parallel with string theorists to explore the frontiers that the latter have opened. Aside from advancing abstract mathematics, the discovery of the ADS/CFT conjecture provides hope that results within a (nonphysical) perturbative string theory may be transformed to a mathematically dual (but physical) nonperturbative theory, such as quantum chromodynamics. If true, this duality would be a major breakthrough, and might by itself guarantee the survival of string theory in some form, even if falsified by experiment.

So even if someone shows that the universe cannot be based on string theory, I suspect that people will continue to work on it. It might no longer be considered physics, nor will mathematicians consider it to be pure mathematics. I can imagine that string theory in that case may become its own new discipline; that is, a mathematical science that is devoted to the study of the structure of physical theory and the development of computational tools to be used in the real world. The theory would be studied by physicists and mathematicians who might no longer consider themselves either. They will continue to derive beautiful mathematical formulas and feed them to the mathematicians next door. They also might, every once in a while, point out interesting and important properties concerning the nature of physical theory which might guide the physicists exploring the actual theory of everything over in the next building.

--

Until experimentalists prove otherwise, Moataz Emam considers himself to be a physicist. His article, "So what will you do if string theory is wrong?" appears in July's issue of the American Journal of Physics.

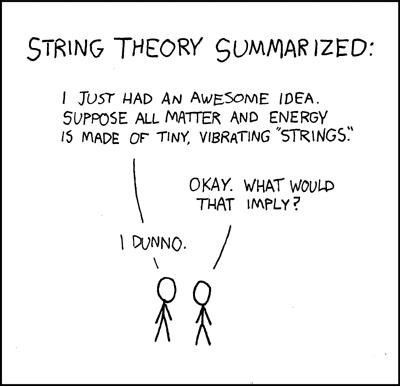

(Image: www.xkcd.com)