An appreciative farewell is due this month to a true scientific radical. While he wasn't a member of FQXi, his enthusiasm for deep cosmological questions, coupled with an absolute willingness to disagree openly - even vociferously! -- with the entire tide of conventional thought marked him as a rare and courageous thinker.

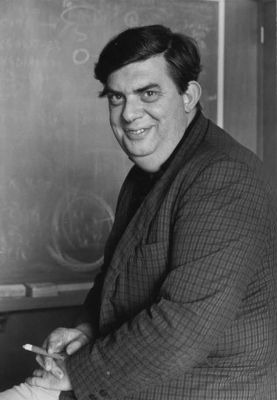

I'm speaking, of course, of Geoffrey Burbidge, grand old man of the alternative astrophysical community, Bruce Medalist, and almost the last remaining bugbear of the Standard Cosmological Model. Burbidge died this month at age 84, having revolutionized the field by first introducing (along with E. Margaret Burbidge, William Fowler, and Fred Hoyle) the notion of stellar nucleosynthesis in 1957. The team laid out the process in one of the great papers of the century, casually known to this day as B2FH. Thanks to B2FH, we understand where the heavy elements came from (contrary to earlier speculation, the Bang produced only hydrogen, helium, and lithium; lovely in their simplicity, but not much more than a primal haze). Burbidge and his coworkers presented compelling evidence that the stars, going through their cycles of life and death, crushed these light elements into more complex forms to be blasted out into space during supernovae. The earth and all its inhabitants, including the one writing this memorial, are evolution's handiwork on the remnants of exploded stars.

Burbidge called me at home a few years back after I had written an article on his dogged opposition to the SCM. At the time I was science editor on a local paper; we had conversed by phone a few times during the writing of the piece, and then I had gone on to other things. I wasn't sure why he was phoning me, but after several minutes realized he was simply keeping the conversation going - a charming aspect of his personality I would later learn was a commonplace among those who interacted with him. On that last call we talked for about a half hour about the "Quasi-steady State" model, his theory that the cosmos is infinitely old, experiencing partial collapses and expansions but no singularity. Perhaps most radical of all, Burbidge was skeptical of red-shift data altogether, which is, as they say, kicking at the big pole of the tent.

The man had a fascinating mind. Are we too quick to assume quasars are "cosmologically distant," and should we (as Halton Arp maintains) take a closer look at their curious visual proximity to active galactic nuclei? Were people in the West more ready to accept the Bang than a steady-state model because the dominant religion had cued them to believe the universe has a beginning in time? Burbidge had even written his own alternative textbook, along with Hoyle and J. V. Narlikar, taking back the SCM and interpreting the data that led to it in an entirely new light.

The net is full of nonsense; everybody knows that. There are as many self-proclaimed geniuses touting a radical cosmology as there are gurus trying to conflate science with superstition. What I admire most about Burbidge, though, is the fact that for all his plying of strange waters he never let go of the rigorous standards of evidence required of credible theorizing. Was he right about SCM? Not many think so, especially after COBE and WMAP. I don't think so myself. But ninety-nine can be wrong; I am reminded of the 1931 pamphlet "100 Scientists Against Einstein." Burbidge's role as gadfly reminds us of how uncertain we actually are of the correct way to read our data; the danger of merely following the crowd; of writing our cultural expectations into nature; and -- exactly because of that -- the necessity of holding on to the steady rudder of objective experiment. Look again: what today thinks it knows may well become the luminiferous aether of tomorrow.