For many years now FQXi member George Ellis has been patiently trying to sell me on the idea of downward causation. While I have never actively argued against this idea, I have come out strongly in defense of reductionism which is generally viewed as upwardly causal. I should note that in recent years Ellis has been arguing against the use of the terms "top-down" and "bottom-up" in favor of "downward" and "upward" since he is not entirely convinced that there is a top or bottom.

George Ellis describing downward causation at the 6th FQXi Meeting.

At any rate, my intense belief in reductionism has likely colored my view a bit. While I still firmly believe in the power of reductionism, I also have come to understand Ellis' point. This year's FQXi meeting was actually a bit of an epiphany for me in this regard. In fact I went out and grabbed two books on the subject, one written by Ellis and one co-edited by him, after the meeting. What I have come to realize is that the two approaches are entirely compatible. In fact I will go one step further and say that they are intimately intertwined in that we can't have one without the other.

August 19, 2019

Downward Causation. Cosmologist George Ellis investigates agency and argues that causation is a two-way process between the mind and lower level biological and physical functions. From the 6th FQXi meeting in Tuscany, in July.

Full Podcast

Let me first lay out what each of these approaches is about. In typical reductionist science, one starts with elementary particles and fields and the most fundamental level and works up from there. The behavior of the particles and fields as they interact causally lead to the formation of atoms. The interaction of the atoms then causally leads to the formation of molecules which, in turn, lead to more complex systems all the way on up to human beings, computers, ecosystems, and governments. The assumption in this view, which has been the overriding view in physics for the better part of the past 400 years (and arguably since the ancient Greek atomists), is that in order to fully understand, say, the human mind, we need to begin by understanding particles and fields. Only by fully understanding the underlying physics can we fully understand the mind, or so the argument goes. In this view, causation is an entirely upward process. The behavior of the particles and fields dictates the behavior of the atoms and molecules which, in turn, dictates the behavior of the cells, and so on. Hence the term "upward causation."

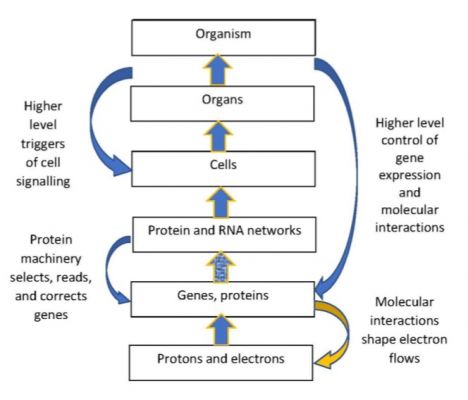

In a more holistic view, higher level structures can affect lower level structures. For example, in computing, the actions of the computer program that is running on a particular computer at a given time are what dictate the behavior of the electrons and electromagnetic fields inside the machine. Each time I type a letter as I write this blog post, it triggers a cascade of signals that dictate just how the electrons are to flow in the circuitry at the most fundamental level. The causation, in this case, is downward. Similar logic and structures exist in biological systems. For example, the contextuality of branching in biological systems represents an example of downward causation. In fact, the term "contextuality" represents much of what downward causation embodies: the behavior of the lower level structures such as molecules, atoms, particles, and fields is determined by the context within which they reside at a given instant.

Upward and downward causation in biological systems.

As another example that Ellis gave in his talk, consider that the abstract design of a plane dictates how the physical object behaves. One of the key aspects of this is the existence of emergent phenomena, i.e. phenomena that only exist at a particular level. For instance, it has recently been argued that the fractional quantum Hall effect is the result of just such a phenomenon.

One of the key results of downward causation is that it allows for learning to take place through a process of adaptive selection and feedback. In fact, in his book, Ellis identifies five types of downward causation, three of which are variants on adaptive selection.

Ellis is the first to admit that a full understanding of how the world functions requires understanding both upwardly causal structures as well as downwardly causal ones. His point isn't to dismiss reductionism. It is simply to point out that reductionism alone will not get us many of the answers we seek in science. Contextual, downward forcing exists and is an important part of any emergent, complex system. In fact he argues that the laws of physics themselves are actually at a rather high level and have a downward effect on the matter and energy within the universe.

I want to take a moment to clarify a point about downward causation that I misunderstood for a long time. A frequent criticism that I have heard of downward causation is that it is nothing more than intelligent design in disguise. As I have come to realize, this is not even remotely true. I suspect it is this misunderstanding that has partly led Ellis to prefer the term "downward" over "top down" since he is not even convinced that there is a top level anyway. His point is made particularly well on the second-to-last slide which is appropriately titled "Conclusion: Evolution is nothing but biology learning how to conscript physics for its purposes". The real world consists of both upwardly causal as well as downwardly causal phenomena. A full understanding of this world, then, necessarily involves understanding both these classes of causal phenomena.