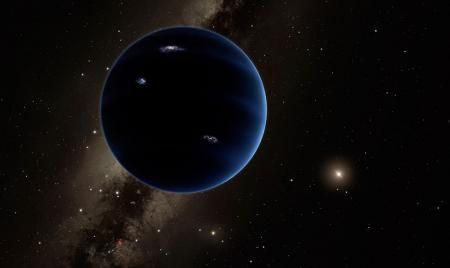

Caltech, R. Hurt, IPAC

On Dec. 8, 2015, two different groups (sharing an author) posted papers to the arXiv announcing the possible detection of planet-sized objects in the far outer solar system (Vlemmings et al, arXiv:1512.02650v2 and Liseau et al, arXiv:1512.02652v2). There was a brief flutter on Twitter and in the media, which shortly died down.聽As far as I am aware, no large-scale effort has begun to confirm or refute these potential detections, and both papers have since been withdrawn, until further data is available. 聽

Six weeks later on January 20, a paper appeared in The Astronomical Journal adducing strong circumstantial evidence, based on solar system object orbits, for a large 9th planet in the outer solar system (K. Batygin and M. E. Brown, The Astronomical Journal Volume 151, Number 2). The media attention was staggering, and the paper downloaded聽243,547 times of this writing. There are almost certainly numerous intense efforts underway to try to detect the object.

While it may be surprising to see much more attention (and resources) directed toward circumstantial evidence for a 9th planet than to direct potential observation of one, this is the sort of decision with which researchers -- and research funders, and journalists -- are confronted all the time. 聽

These decisions are, in essence, predictions about how things are going to unfold; this has gotten me interested in how to better solicit and aggregate expert predictions in science and technology, and helped motivate a new project I and several other physicists have been developing, called Metaculus.

To be more specific, there is an important class of decisions that can be posed in the form of "what is the expected聽return on my investment of time/effort/attention/funding in X?" For some science-based examples:

-- "What is my expected return in using my time on telescope X to search for the planet suggested by this data?" Here the potential "return" is fame and satisfaction at discovering a planet.

-- "What is my expected return in skimming/reading/studying this new paper?" Here the return might be insight gained, entry into a promising new research direction, etc.聽

-- "What is the expected return in funding this research grant?"聽Here, the return could be papers published, talks given, meetings run, or more abstractly intellectual impact on a field or set of questions.

-- "What is the expected return on building this instrument?" The impact here would be scientific discovery, possibly measured by papers, citations, etc.

A central idea in these questions is that of expected return. Most simply, this could be the likelihood of success times the return if successful. Or, if there are multiple possible outcomes, it could be the sum/integral of the probability of each outcome times that outcome's impact.聽

The idea of high expected return (per dollar) is part of FQXi's core philosophy (and grantmaking criteria). To make a financial analogy, government funding agencies tend to purchase the equivalent of a diverse-but-safe portfolio of bonds and index funds: decent returns, fairly safe. These agencies tend not to fund the science equivalents of startup companies -- projects where the chance of major success is fairly low, but the impact if successful is very high. We believe that in the science, as in the corporate, world, both types of investment are very important, and one role of FQXi is trying to fill in this end of the research funding portfolio. 聽

Evaluating the "probability of success" is, though, rather difficult.聽It's 聽often not hard to assess which of two projects is more likely to be successful.聽For example, I would say the Wendelstein 7-X fusion experiment and subsequent efforts are more likely to lead to useful energy generation than Brillouin Energy's LENR experiments. But how much more likely?聽Ten times?聽A thousand? A million? The 7-X's funding is probably about 1000 times higher, so which experiment has the higher per-dollar expected return on investment depends on this likelihood ratio!聽Or what about tabletop quantum gravity experiments versus a bigger version of the "holometer"?聽

The idea of Metaculus is to generate quantitative and well-calibrated predictions of success probabilities, by soliciting and aggregating expert opinion, and by (in the process) helping people improve their skills at quantifying and predicting impact. Metaculus poses a series of questions, for example "Has a new boson been discovered at the LHC?", with relatively precise criteria for resolving the question after a specific time. Users are invited to predict likelihoods (1-99%) for these questions, and later awarded points for accuracy in their predictions. Studies show that by carefully combining the predictions of many users, better precision and calibration can be achieved.

My experience so far suggests to me that there are several ways a prediction platform like this, when applied to scientific research, can be complementary to traditional peer-review. The effort of creating precise criteria for 'success', and in trying to assign numbers to success likelihood, has a quite different feel than just reading to understand whether a paper/proposal is intellectually sound or correct. It also makes me realize that in all of the peer review and assessment that I have done, I've never been asked (or asked someone) to supply a number like "what is the probability that X will be the result of funding/publishing Y?" 聽Since that's a significant part of what peer review is, isn't that a bit odd?

Perhaps there is an opportunity for real improvement here. A recent study made the case that prediction 'markets' are quite effective -- and more effective than surveys even of experts -- in forecasting whether given research (in this case in psychology) would be successfully reproduced (PNAS, Vol 112, no. 50).

I'm very interested in everyone's ideas for how something like Metaculus could be used in trying to make the biggest impact we can out of the limited resource society throws in the direction of us scientists -- please comment!