At about 1 AM GMT on April 20, 2007, the Universe split into at least 32,768 nearly-identical copies. How? And did it really?

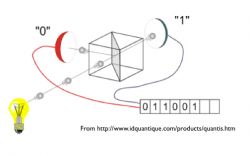

The event was precipitated by yours truly gathering a quantum-mechanically random number between 1 and 10,000. Generating this number required making at least 15 quantum measurements, each yielding one random bit. In the course of each measurement, a solid-state device effectively fired a single photon through a half-silvered mirror, as shown in the first figure.

The photon, being a quantum object, corresponded to a wave-function, and each firing then corresponded to a photon wavefunction that split into two superposed pieces, one of which hit the ‘0' target and one of which hit the ‘1' target in the figure.

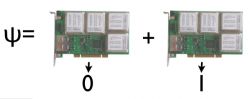

However, thinking a bit more carefully, the ‘mirror', the targets, and in fact the whole computer card, while big, should still be fundamentally quantum-mechanical. Thus what was really created was a superposition between one state describing a computer card that supplied a ‘0' bit, and one that supplied a ‘1' bit.

But then, carrying this thinking forward, by asking for this random number, I really created a superposition of internets, and computers, and Anthonys, in one of which a ‘1' bit appeared, and one of which a ‘0' bit appeared. And after 15 such measurements, a superposition of 32,768 Anthonys was formed. Further, on the basis of the number between 1 and 10,000 (which served as the ‘seed' for generating further pseudo-random numbers), a piece of software run by Anthony determined the results of the FQXi minigrant lottery , and so – in the wavefunction -- there are at least 10,000 copies of each FQXi minigrant applicant, some of which correspond to applicants who get their minigrants, and some of which do not.

Now, some questions. First, can we observe more than one of these distinct outcome happening? No. The large number of degrees of freedom involved, including the ‘environment', mean that – by a process called ‘decoherence' - all interaction between the branches will be suppressed. Only one gets experienced at a time. Second: Are all of these ‘branches of the wavefunction' equally real? Some interpretations of quantum mechanics say yes, some say no. Both are troubling.

If no, then we might ask: at what stage did one of them become real, and the other not? And what is this ‘realness' that goes beyond the mathematics of the wavefunction? The unpleasantness of both questions leads some thinkers to say ‘yes' and embrace various versions of the ‘Many Worlds' interpretation of quantum mechanics.

But if yes, there are even more questions. In particular, what determines what actually gets experienced, and why do the quantum probabilities apply? The core of this problem can be seen as follows. Suppose a mad scientist came to you and told you that he had built a teleporter. But due to some intrinsic constraints, it would create two nearly-identical copies of you. One would be teleported far away, to whatever pleasant destination you wish, but the other would be forced to endure a prolonged and agonizing death. (There is a recent movie along these lines, but I will not mention it for fear of including spoilers). I, and I suspect you, would be very hesitant to enter the machine: isn't there a good chance that the next thing ‘you' will experience is painful execution? Now, however, the scientist tells you "don't worry! I have a little dial I can set, and the probability of your ending up in the pleasant place can be set to 99.999999%; the chance of you being the one that dies can be made tiny!"

I don't know about you, but I would still not set foot in the machine: how could he possibly "send" my personal experience one way versus the other with such confidence?

This, of course, is just what Many Worlds asks us to believe: that in a quantum measurement both outcomes occur, and are experienced by two otherwise equivalent observers. Yet you are supposed to believe that the probability of your becoming one versus the other of those observers is governed by the probabilities of quantum mechanics (the ‘Born rule'). For the life of me, I don't see how this can make sense.

So while I'd like to believe that FQXi has funded all of its minigrant applicants, I don't REALLY believe that it has. But hopefully the applicants do, and can take great comfort in this.