The Perils of Peer Review

How 'publish or perish' culture has encouraged dubious practices, from misattributing credit, to plagiarism and fraud.

by Foundational Questions Institute

March 10, 2025

"Publishing has gotten very profitable—and capitalism is ruling scientific journals over science," says Raissa D'Souza, a computer scientist and engineer at the University of California, Davis, who is a member of the board of reviewing editors for the journal

Science, published by the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) and a founding editor of the open-access journal

Physical Review Research, published by the American Physical Society (APS). The science-publishing industry is estimated to be worth US$24 billion, with 40% profit margins that would make tech giants envious. Yet many academics argue that most journals are no longer fit for service, and, in some cases, are actively toxic, exploiting researchers. "They have a whole ecosystem where they try and view the scientist almost as prey to be consumed," says D'Souza.

This is the second part in a series of articles discussing the values of, and the problems with, the peer-review system at the heart of scientific journals.

Part 1 of the series discussed the history of scientific publishing—from its inception 360 years ago this month to today—and how good journals can still provide a valuable service, sifting through the deluge of online preprints and curating high-calibre studies. But many researchers feel that the peer-review system is now strained to breaking point and that, in general, journals are failing to separate high-quality work from weak, or even false, studies. Under intense pressure to publish paper after paper, some authors are gaming the system to boost their publication metrics in order to impress funding agencies and universities. As paper retractions skyrocket, there are also concerns surrounding the rise of paper mills—organizations selling authorship on fake papers—the incorrect attribution of credit, plagiarism, and citation and review fraud. This second part of the series delves into these allegations, based on an FQxI survey of 73 of its member scientists and a consultation with multiple researchers and journal editors, who spoke to reporters

Brendan Foster,

Miriam Frankel,

Zeeya Merali and

Colin Stuart.

In an ideal world, writing papers to communicate research should be a rewarding experience for the scientist: the culmination of years of research and the opportunity to disseminate findings for others to build on. Submitting the drafted paper to a journal for review can be stressful, but ultimately, the feedback should be constructive. "The goal is always to have an improved product," even if at times, going through peer review is a "pain in the ass," says Miguel Roig, a psychologist at St. John's University, in Staten Island, New York, who is a member of the board of directors of the

Center for Scientific Integrity. Reviewing the papers of other scientists should also be enjoyable, says Roig. "I always looked forward to peer reviewing because it was a way for me to learn and be on top of the game."

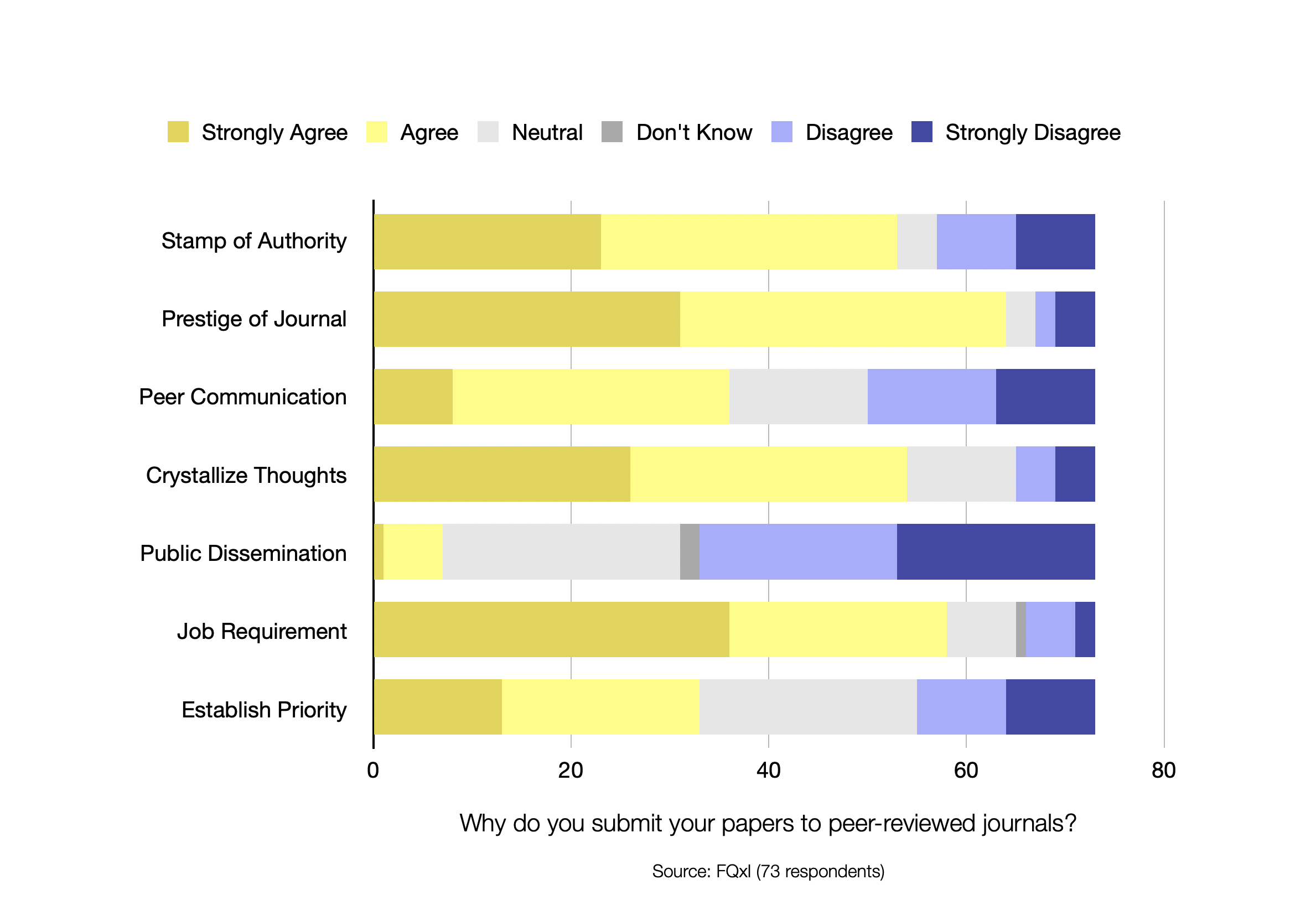

Indeed FQxI's survey revealed that scientists do see a number of positive reasons for submitting papers to journals, rather than just posting preprints: 88% of respondents said that publishing in certain journals adds prestige to the paper; 74% of respondents said that the process helped them to crystallize their thoughts; and 73% said that journals provide a legitimate stamp of authority. When considering all their paper submissions over the past five years, 58% of respondents said that the quality of their papers was improved by the review process.

A 79% majority of survey respondents also said that they are required to publish in peer-reviewed journals as part of their career progression—and it is this motivation that, some have argued, can become problematic.

FQxI survey respondents were asked their reasons for submitting papers to peer-reviewed journals: to give their work a stamp of authority; because publishing in some journals carries prestige; to communicate with their peers; to help crystallize their thoughts on a topic; to disseminate their work to the public; because it is required for the career progression; and/or to establish priority of ideas.

FQxI survey respondents were asked their reasons for submitting papers to peer-reviewed journals: to give their work a stamp of authority; because publishing in some journals carries prestige; to communicate with their peers; to help crystallize their thoughts on a topic; to disseminate their work to the public; because it is required for the career progression; and/or to establish priority of ideas.Many researchers worry that hiring and promotion committees at universities, and funding bodies looking to dole out money for projects, place too much emphasis on journal publications as a measure of an academic's worth, leading to a 'publish or perish' culture. Specifically, these bodies base their decisions on ostensibly objective 'publication metrics' that measure the volume of papers that an academic produces, the reputation of the journals in which those papers appear, and the number of citations the papers receive. These metrics include the researcher's '

h-index' (a measure

proposed in 2005 by physicist Jorge Hirsch to help assess the amount of publications produced by a researcher and how often these publications are cited) and the 'impact factor' of the journals they publish in (a measure of the citations garnered by papers in that journal). For many, this bean counting comes at the expense of considering the actual content and merits of scientists' research and their other professional skills and achievements. In FQxI's survey, 63% of respondents said that they felt that those who have power over their career trajectories judge them more by publication metrics than by the quality of their work. This numbers game can pressurise academics to churn out high quantities of low-quality papers.

We need people, faculty, and scientists, to start wanting to understand substance over just sheer numbers of publications.

- Raissa D'Souza

But some question whether publication metrics are useful, at all. "They measure how well your research fits with the current trends, and that, essentially, is it," says Kasia Rejzner, a mathematician at the University of York, UK and president of the

International Association of Mathematical Physics. "We need people, faculty, and scientists, to start wanting to understand substance over just sheer numbers of publications," adds D'Souza.

This publish-or-perish culture also breeds bad-faith practices, tempting authors to game metrics and, in some cases, to commit full-blown fraud. Only 44% of FQxI survey respondents expressed confidence that even the best journals in their fields discourage such negative practices, with confidence levels dropping to just 12% when considering all journals in their field. D'Souza reports that her students are often flabbergasted at, and daunted by, the metrics of some scientists. Some students showed her a researcher boasting 50,000 citations and an

h-index of 105 (for comparison, Hirsch had noted that 84% of Nobel prize winners had an

h-index of at least 30). D'Souza's response to her students was candid: "There are two ways to get that

h-index and those citations: be brilliant or work the system."

It appears that many academics are indeed working the system. An

analysis by

Nature found that more than 10,000 research papers were retracted in 2023—predominantly papers from Saudi Arabia, China, Pakistan and Russia—with retraction rates trebling in the past decade. Retractions are not necessarily a bad thing and can happen when researchers find accidental mistakes in their work, or bugs in their software, for example, notes Rejzner. Such cases should be commended as a sign that science is working well and self-correcting. But increasingly, the cause of retractions has been systematic fraud.

If the topic is specialized it's very hard to tell whether the paper is written by a human or not.

- Fengyuan Liu

The push to publish sees many scientists employ cheeky, rather than fraudulent, tricks. For instance, scientists can up their paper count by 'salami-slicing' their research, so that they can report their findings in multiple papers. "We publish too much," says Rejzner. "Three papers could be one paper." But more alarmingly, the pressure to publish has also encouraged the rise of shady paper mills. "These are basically services where you can buy authorship on manuscripts that are to be published," says Tony Ross-Hellauer, leader of the

Open and Reproducible Research Group, at the Graz University of Technology in Styria, Austria.

Plagiarism, fabricating or falsifying research, and conflicts of interest are also on the rise, says Roig. "Fraud seems to be on the increase, I'm sorry to say."

This is coupled with a worrying trend of using large language models, such as ChatGPT, to generate papers and peer-review reports. "There are people out there asking AI to write papers and submitting to very low quality journals," says Jorge Pullin, the founding editor of the APS journal

Physical Review X. "If the topic is specialized it's very hard to tell whether the paper is written by a human or not," adds computer scientist Fengyuan Liu, a doctoral student at New York University in Abu Dhabi, who has investigated academic-publishing fraud. "That's going to be a big problem," he says.

The Problems of Peer Review

Ivan Oransky of Retraction Watch and arXiv discusses whether science publishing is broken.

Full Podcast

Another widespread problem is the increase of peer-review rings, where reviewers collude to give each other favorable reviews. Publishers Wiley and Hindawi

retracted over a thousand articles in 2023 because of such cartels. Physicist Abhay Ashtekar of Pennsylvania State University in State College, who has sat on multiple editorial boards in his 50-year career recalls a less common and quite bizarre case of peer-review fraud that he encountered. It was discovered that an author had been publishing papers on the same topic, under two different names. Editors at a journal unwittingly contacted him under his fake identity to review the papers that he had written under his real name—after a computer algorithm had highlighted his phoney persona as an expert in the area. The fraudulent physicist then gave himself a glowing review report. Ashtekar believes that journals' over-reliance on bad algorithms for reviewer recommendations is at the root of many of the problems with peer review. "Referees are selected more or less by computer," rather than by human editors who are subject-area experts, says Ashtekar. "I really think this should not be the case."

It's even worse if bad papers are not spotted, however. "Papers that are literally false don't get retracted as often as they should," says Ivan Oransky, who tracks misconduct on the

Retraction Watch site. As a result, scientists often waste time chasing dead ends and eventually leave science in frustration, he says. "Those are some of the people who are honestly the most intellectually rigorous, and we should want them in science."

The drive to be seen to have authored as many published papers as possible can also tempt researchers to claim credit on papers where they did not significantly contribute—or even contribute at all. "There are some leaders of institutes who appear on every paper that institute publishes, which is totally unfair," says Ross-Hellauer.

There are many horror stories of senior researchers bullying younger colleagues to add their names to papers to which they did not contribute, or taking younger scientists' names off papers, even though they did the bulk of the work. "What's sad is that often the way that you come to understand the politics of publishing is the first time you get burnt for sharing ideas openly in the spirit of scientific collaboration with senior people," says D'Souza. "Those senior people take ideas and publish them without giving any credit to younger people."

The way that you come to understand the politics of publishing is the first time you get burnt.

- Raissa D'Souza

In FQxI's survey, 56% of respondents expressed confidence that papers published in the best journals in their field correctly attribute credit, but that confidence level dropped to 32% when considering all journals in their field. Some journals attempt to deal with the issue by asking all authors on a paper to specify their contribution to the work. However, as one FQxI member noted, these contribution statements can cause friction within labs and among colleagues, and some unethical senior scientists already discourage juniors from publishing in journals that demand such declarations.

Another nefarious tactic to manipulate metrics is to artificially inflate the number of citations to your paper. One way is through citation rings. "If there is a critical mass of people who cite each other, you can create a high citation rate," says Rejzner. Reviewers and editors have also been known to coerce authors to cite their papers as a condition of publication.

Is Science Becoming Less Disruptive?

The proportion of research papers and patents describing big leaps is going down. Zeeya Merali, Ian Durham and David Sloan discuss.

Full Podcast

Some cases are quite extreme.

Retraction Watch raised the alarm in a high-profile scandal involving computer scientist Juan Manuel Corchado, rector of the University of Salamanca in Spain, in 2022, noting that nearly 22% of his citations were to his own work. In 2024, the Spanish newspaper

El Pais published a fragment of a conference presentation that Corchado gave in which he cited himself over 100 times. Many of his papers are now under suspicion, including dozens published by Springer Nature, but Corchado has

publicly denied wrongdoing and stated that the allegations are part of a "smear campaign."

In 2024, Liu and colleagues

revealed evidence that citations can be bought in bulk from citation-boosting services, manipulating Google Scholar, the free web service that many universities use to find information regarding an academic's papers and citations. The team went undercover as a fictional author and bought 50 citations. "It's not clear exactly how many people are buying citations," says Liu, "but I suspect it's a lot."

In academia, it's not just what you say, it's where you say it that's important, with academics also believing that they must publish in journals with high impact factors to succeed. "My young colleagues feel like to get a faculty job, they need a

Science or

Nature publication, and then to get their tenure, they feel like they need these as well," says D'Souza. In 2023, China

overtook the US as the biggest contributor to nature-science journals. Chinese scientists are routinely given personal bonuses for getting into prestigious journals, says Oransky. "Somewhat underpaid academics could literally double their salary by publishing a few papers in higher impact factor journals."

But a number of FQxI survey respondents expressed concerns that the need to target prestige journals encourages scientists to overhype results. At the same time, scientists are discouraged from publishing negative results. "In certain fields, particularly medicine, positive results mean more grants, more patents, more commercial success," says Oransky. "So every incentive is maligned." This results in a lot of time being wasted too, with scientists unnecessarily repeating experiments that have already been done, but were never reported.

There are also cases where even people who have been published in high-impact journals are not correctly cited in later works by others, diminishing their credited contributions to their field. D'Souza mentions a recent case of a young researcher she knows who did "groundbreaking work," published a proof-of-concept paper in the Springer Nature journal

Nature Communications and obtained patents. He then came to D'Souza distraught when he saw a paper in

Science in which others claimed to be the first to have done the same thing. The authors had cited him, "but they gave a little throwaway citation, as one of around 20 to have done background work," she says. D'Souza's advice to her junior colleague was to let the issue drop. "It's not in your best interest to take on giants in the field," she told him. "You want to be known as a scientist who created transformative innovation in the world, not as a scientist who brought down a giant through legal channels."

At the heart of many academics' discontent with journals are the high costs of publishing that must be borne either by the author or the reader. Traditionally, university libraries paid high subscription fees to particular journals, so that their members could access the papers. But many journals now opt for open-access publishing, allowing everyone to read the article for free, a move that is largely welcomed by the research community. The price for this is usually paid by authors, however, who are charged an "article processing fee" to publish, which can range from under US$100 to $10,000. "The publication fees are astronomical," says Marcus Huber, a physicist at TU Wien, in Austria, who

co-founded the non-profit journal

Quantum. (

Quantum also charges a processing fee but, like some other journals, it allows authors to waive the fee, if they do not have sufficient grant funds to pay.)

"When I tell some folks—non-academics—that I sometimes have to pay to get my work published, they look at me as if to say, 'are you out of your mind?'" Roig says.

Some journals are run by non-profit organisations and scientific societies, such as the AAAS and the APS. A handful of respondents to the FQxI survey commented that they actively choose to publish in, and review for, such journals, over those run by corporate publishers. Many respondents noted that modest fees are understandable when charged by non-profits. But many commented that it seems particularly egregious when large fees are charged by for-profit megapublishers, especially given that the costs associated with publishing articles

have been estimated to be well below $1,000. "Publishers regularly report around 40% profits year-on-year, which even in comparison with Apple is ridiculous," says Ross-Hellauer. "They could definitely decide to take less profit and invest more in the system."

When I tell some folks—non-academics—that I sometimes have to pay to get my work published, they look at me as if to say, 'are you out of your mind?'

- Miguel Roig

Pullin notes that the research itself is often publicly-funded and thus questions why private industry is allowed to enter at the last step of the research process, in which the results are communicated to other academics and to the public, and make money from it. Making things worse are 'predatory' journals that charge humungous fees, but provide little to no vetting for quality. "They just want to make money and they accept almost anything," says Pullin. Such journals exacerbate the spread of misinformation, highlighted at the height of the pandemic, says Roig: "People would publish garbage about Covid in a 'journal,' right?"

D'Souza, whose first editorial assignments were at the journal

Scientific Reports, now under Springer Nature, is increasingly nervous that huge for-profit publishing companies are gaining a tighter stranglehold on researchers. "The merging of

Nature and Springer became a behemoth in the scientific publishing world, and there are all kinds of baby

Nature journals now and they try to keep things within their fiefdom," she says. "They have marketing efforts, so when you submit, but you can't get into

Nature, they'll say, try

Nature Communications, and if you didn't get into

Nature Communications, they'll be like, try

Nature Human Behaviour, and if you don't get into

Nature Human Behaviour, try

Scientific Reports." (FQxI contacted

Nature for comment for this series from a current editor, but

Nature declined the invitation.)

Influencing such big players to change their business model won't be easy, warns D'Souza, because they are monsters of academics' own making. "We set up the publishing system to build up gatekeepers," she says. "But now they can then use those powers to build their legacies, control funding and suppress new ideas."

The final part of this series, "How To Fix Peer Review," investigates ways to bring integrity back to scientific publishing, by compensating reviewers, instituting post-publication peer review more widely, and shifting the culture of academia back towards valuing scientists and science, over metrics.FQxI publishes a book series in partnership with Springer Nature. Miriam Frankel and Zeeya Merali have reported for Nature

and Zeeya Merali has reported for Science

.