It's a summer for celebrating the moon. As anyone interested in our space-faring future knows, we're commemorating this month the 40th anniversary of humanity's first stroll on one of the heavenly bodies.

It's a mighty achievement, and comes with a faint bitterness as well. (Moon soil, I am told, smells a bit like wet fireplace ashes.) That bitterness exists for those of us who think the Apollo program should never have been scrubbed in '75--with Apollo 18,19 and 20 never to be launched at all, and our first fragile toehold on the solar system relinquished for low-earth orbit affairs. For all the shuttle program's achievements, and I have sung them here, it's a pity to have reached our satellite and then let it go again, like a balloon whose string you once held.

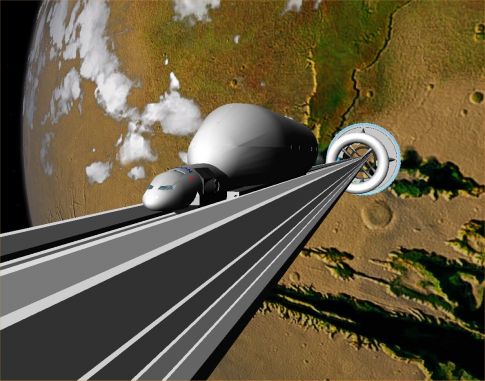

And it's a greater pity not to have used it as a springboard to farther destinations. At a gathering this month of Apollo 11 astronauts at the Smithsonian's Air and Space Museum in downtown DC, the reigning sentiment was that even returning to the moon now would be anticlimax. Instead, we need to press for Mars.

Collins: "Sometimes I think I flew to the wrong place. Mars was always my favorite as a kid and it still is today. I'd like to see Mars become the focus, just as John F. Kennedy focused on the moon."

Aldrin: (the best way to pay tribute to Apollo 11) "is to follow in our footsteps; to boldly go again on a new mission of exploration."

These are the sentiments of heroes. Flying to the moon wasn't--or shouldn't have been--a one-shot deal that we did in order to rest on its laurels for half a century. It was the opening of the door, if only by a crack, that leads to the greater celestial highway.

When the Apollo 11 astronauts made a Mars pitch to President Obama, the response was, however, lukewarm. Obama is interested in showing that "math and science are cool again," which I can only applaud, but apparently has no interest in sending Americans into deep space. Given our financial wreckage, it's not a big surprise. But what would make science cooler in the eyes of the next generation than a successful Mars trip? What would give us technological and economic returns whose nature we can't even foresee? What else would serve to unite our fractured people in an Apollo-era national cheering session?

There's an intriguing discussion on just these issues--to the moon? To Mars? Or to reign it in?--on Tom Ashbrook's show *On Point*, with three distinguished guests: Robert Zubrin, author of "The Case for Mars," David Kring, former director of the NASA Space Imagery Center, and Harrison Schmitt, who flew on Apollo 17. Well worth a listen.

As a side-note for those interested in all things lunar: I can recommend the sci-fi mindbender "Moon," starring Sam Rockwell and Kevin Spacey's voice. It begins in the relatively near future with a lunar mining operation harvesting helium-3 from the regolith for fusion energy on earth (a sensible premise, as the solar wind has been firing that rare isotope into the moon for millennia--though why you would need to be on the far side to find it is unclear). Just as our hero is wrapping up his three-year contract, he finds the body of another astronaut lying on the surface . . . one that looks suspiciously like . . .

"Moon" is a fusion product itself--it's part "Solaris," part "Space Odyssey," with some of the better plot twists by Phillip K. Dick thrown in. But that's a fine pedigree, even for derivative work. There's good speculative science here for those who appreciate it, of the type that makes us ask fundamental questions about identity, technology and the perils of the post-human.