FQXi researchers pride themselves on pushing the boundaries of what's known--positing theories at the edge of what we can conceive. Unfortunately, this almost inevitably involves hypothesizing things that lie far beyond what can currently be tested. Many are waiting for results from the LHC or from some new telescope or the other to provide some evidence for or against their ideas. Still others can't promise that their predictions can be falsified by any experiment currently envisaged. As such, theorists are often criticised for letting their ideas run wild. So it's nice to see that one of FQX's astronomers, Harvard's Avi Loeb, is making an effort to go back and double check the observational evidence for a theoretical entity that seems to have transitioned from science fiction to science fact over the past decades: the black hole.

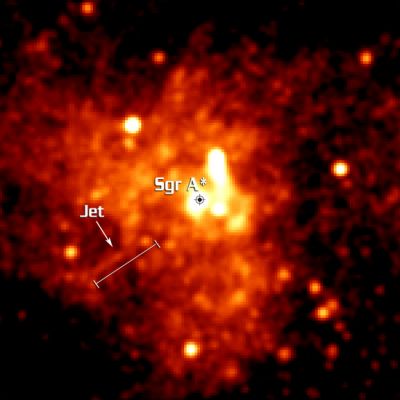

Chandra close up of Sgr A*

Black holes may have seemed wacky when they were first proposed, but they are now so firmly embedded in public consciousness that most current headlines referring to them do so metaphorically, usually to describe our dire financial straits--"Billions Go Down a Black Hole," "Black Hole balance sheets," "Budget leaves a Black Hole." (Possibly there's something weird physics-y time-travel effect happening with the second headline. As I access the page now, the news article is running with _tomorrow's_ date.)

As far as black holes in physics are concerned, most assume they exist--some even producing simulations of what it would look like to fall into one. Every so often, though, physicists offer up controversial alternative interpretations to the evidence for black holes, including wormholes, stars built out of dark energy, or bubbles of exotic dark matter. So it's worth seriously re-examining the evidence we have for the black hole at the center of our galaxy, as Loeb is doing.

In 2006, Loeb won an FQX grant to hunt for intelligent alien life. (You can read more about the search in "Eavesdropping on ET.") Loeb and his colleagues have been busy releasing a bunch of papers, which have been popping up in the news over the past couple of weeks, talking about rogue black holes munching their way round the Milky Way. (Sometimes I wonder if Loeb chooses his research topics based on the plots of 1950's B-movies. If his search for ET comes back with a warning about rampaging vertically-enhanced females, I will be very suspicious.)

Weak jokes aside, Loeb does great work and is aware of the importance of using the latest observational techniques to rigorously check what many take for granted, for instance, the existence of "event horizons"--the surfaces that are believed to surround black holes, beyond which light cannot escape. That's something that New Scientist's David Shiga picked up on when he eschewed writing about some of Loeb's more headline-grabbing findings to report on his paper from March with Avery Broderick and Ramesh Narayan, reviewing our latest observations of Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*), the supermassive black-hole candidate at the center of our galaxy. Churning through the evidence, they conclude that it does appear to be a black hole shrouded by an event horizon, as commonly supposed. (For those who regard black holes and event horizons as mundane, Shiga points out that the observations don't rule out the possibility that Sgr A* is a wormhole.)

image3#It's sobering to note that the earliest theoretical paper on event horizons that Loeb refers to in his paper was written as far back as 70 years ago, in 1939, by J. Robert Oppenheimer (yes, that J. Robert Oppenheimer) and his graduate student Hartland Snyder. Oppenheimer is now remembered as the "Father of the Atomic Bomb," but he was also one of the first researchers to seriously look into whether the bizarre entities predicted by the equations of general relativity actually could exist. Looking for the root of the idea of black holes takes you back far further, to the eighteenth century and English geologist John Michell. (The image shows the title and an excerpt from his 1783 paper, which first described the concept of a black hole in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Photo courtesy of the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, vol. 74, pp. 35. 1783.)

The moral of the story is clearly that for FQXers and others hoping for experimental or observational support for their ideas, patience--possibly stretching over centuries--is a virtue.

Finally, I can't talk about black holes without mentioning the man whose name is almost synonymous with them, having laid much of the groundwork on the topic and famously losing a bet about the fate of information about things that fall into black holes. Stephen Hawking's ill health has been in the news since he was rushed to Addenbrooke's Hospital in Cambridge with a chest infection earlier this month. The thoughts of everyone at FQX are with him and his family, as we wish him a full recovery.