I'm posting this month from Italy, home-base of one of the most influential metaphysical systems in history--Roman Catholicism--and home to one of the most important names in physics: Galileo Galilei.

The light in Florence is of a clarity I have never experienced; I can see why this is a haven for painters. But leave that aside. If you have ever been here, you know.

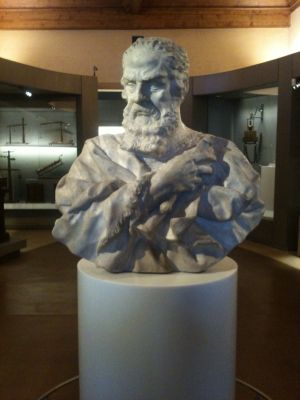

After saturating myself with the products of unparalleled artistic and religious expression, I visited the rather modest museum to Galileo, tucked in beside the bubbling Arno. These are some images from inside.

These are Galileo's fingers, kept under glass very much in the manner of reliquaries. Odd to see a person who so troubled the Church preserved in a style set aside for saints. One wonders whether enough traces of DNA remain in those desiccated bone cells to one day resurrect the great man; he would certainly be surprised to find himself, say, in the year 2115, and to discover how completely vindicated he was. (I know, I know: cloning doesn't "bring back" the same person. Just play along, huh?) How ironic would it be if his Inquisition-banned books contributed to the formation of a scientific culture that, centuries later, gave him that very thing to which the Church had laid claim--life after death?

Ah well. At least his discoveries live on . . .

Here is the actual telescope that caused all the trouble, or one just like it. It is astonishingly small; about the length of a pool cue, perhaps twice as thick. That's it.

Is there a moral in this unprepossessing object? Granted, it was high-tech for its day. But perhaps the moral is that revolutions in knowledge come not from advanced instrumentation alone, but from ability to think outside the dogma--to turn that ship-spying device toward the sky, as it were. (And to admit what you are seeing--no mean feat in itself. Galileo famously complained to Kepler that some of his opponents in the heliocentric debate refused even to look.)

Perhaps this is a moral for our day, as well. We may not be able to get any closer to confirming or disconfirming String Theory, for example--which, despite its general popularity in the press, is still entirely hypothetical; it bears repeating that the whole construction may be nothing more than a complex exercise in mathematics--without colliders that can reach unheard-of energies. If the kind of energy required turns out to be permanently inaccessible, we may be at an end on our quest. In that case, even if String Theory is true, we'll never know it.

Or . . . there may be a conceptual shift somewhere down the road that allows new understanding. To be sure, it won't happen without empirical data. History is replete with grand claims about the universe that cannot be tested, and so aren't worth terribly much; with no telescope at all, Copernicus' system itself might have remained "a complex exercise in mathematics," as Osiander wanted it to be. But perhaps Galileo's modest little device is whispering that the critical revolutions are the ones that happen inside the mind.

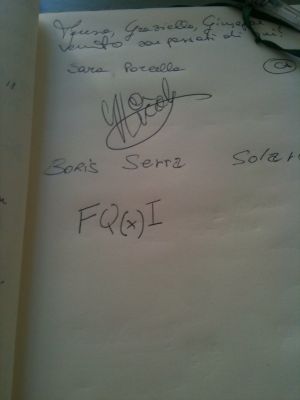

Last thought before we leave the museum: I signed the guest book with the FQX(i) logo. I'd like to think the great revolutionary would have approved.