What "shape" is the universe? Cosmologist Mark Wyman ponders whether the cosmos is smaller than we might imagine and "shaped" like a human. And how we may never know for sure.

From Mark Wyman:

If I look up into the night sky with a strong enough telescope, could I see the back of my head?

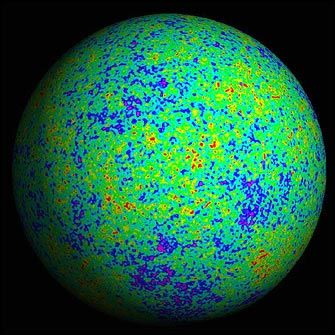

Cosmic Microwave Background

Sounds bizarre, but I was reminded of that question when I came across a new paper looking into the "shape" of the universe by Mota, Rebouças, and Tavakol. In theory, if the universe is finite and relatively small, and wrapped up on itself in a weird way, you could see the back of your head, if you looked out far enough. In practice, light goes too slowly--or the universe is just too big--for that to happen, exactly. But we could see repeating patterns in the relic radiation from the big bang, the so-called cosmic microwave background (CMB) radiation. By looking for those, we can ask the same questions: Is the Universe finite in size? And if so, what is its shape?

On the face of it, this seems like a question only a nut would ask. Actually, it may not be so crazy--but we can come back to that in a moment. The fact is that universe very well could be finite in size. FQXi's Max Tegmark, among others, suggested that the universe might be doughnut-shaped a few years ago, while others think it may be shaped like a soccer ball or some other strange shape. If its size is just small enough, there could be telltale signs that we could spot in the sky--we just haven't noticed them yet.

At this point, the cosmologically savvy may ask--don't we know something about the shape of space already? And they would be right. We now know a lot about the "curvature" of space, which is controlled by how much matter it contains and determines the universe's ultimate fate. A universe with a large density of matter and a large curvature would eventually collapse back in on itself. Luckily, we now have good evidence that the universe is flat as a board; so it looks like we'll be avoiding a big crunch.

(Image: University of Arizona Math Department)

Here, we're not looking at curvature, but at a different aspect of the shape of the sky. To use technical language, the question is: what is the universe's "topology"? Topology is the mathematical study of shape, taking into account the way that an object wraps around on itself and the number of holes passing through an object. For instance, doughnuts and coffee cups have the same topology because they each have one hole. (There's a nice animation showing a coffee cup changing into a doughnut here.) You could say that humans are topologically doughnuts because we also have one "hole" passing through us.

If the universe does have a measurably finite size, how could we tell? The universe isn't literally doughnut-shaped or soccer-ball shaped (or indeed human-shaped), but if the universe is wrapped up in a complicated manner, then light that appears to be travelling out of one end of this compact cosmos would immediately re-enter it from the opposite side--effectively allowing us to see the backs of our own heads.

The way that this would show up is that we would see repeating patterns in sky--that is, we could find two patches of the sky that look identical because they are identical. By correlating where these "circles in the sky" match up, we could figure out how the universe is connected. That pattern of connections would tell us what the basic shape of space was.

Pondering the shape of the universe

There's a funny story about this. One of the principal scientists on the team for the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP), the space-based telescope that has given us our best picture of the CMB by far, wanted to look for these patterns. Since he had the data before anyone else, he figured he should take a look. So this guy started his analysis running one night before he went home; the next morning, he gets to the lab, and what's on the computer screen? A series of positive detections!

The universe is finite! And he found it! He gets excited, thinking he's going to be famous. But then he looks at the directory that the data files are in... He'd made a mistake. He hadn't been looking at the real universe data. Because analyzing the data from these experiments is complicated, cosmologists practice their analysis techniques by making fake data sets with various effects put in by hand. He had been using one of his fake data sets he had made months earlier to test this very analysis, not the real data.

But let's say we do see this crazy pattern in the future--so what? Besides the wow factor and the possibility of making the discoverer famous, what would we gain? Well, for a start it could tie in with string theory (pun intended). String theory famously tells us that the universe contains 10 dimensions, with all but the three large dimensions curled up in tiny twisted patterns. However, if the universe started out super small, which we know it did, the three huge dimensions we have also were originally curled up in a twisted pattern, too. So, when our three dimensions got picked out and blown up, they carried with them the shape that they had back in the earliest time. This is the shape we hope to see from research like the recent work by Mota, Rebouças, and Tavakol, outlined in their paper.

In it, the authors look for identical patches that fall exactly opposite each other in the sky. This isn't the only possible pattern that would imply a finite universe, but it's the simplest, and computer resources are limited. Moreover, this particular pattern is the only one consistent with the flatness of the geometry of the universe that we can directly see. A more complicated pattern of "connections" in the sky would imply a twisted universe--in all senses of the world--and we happen to know that the universe is a pretty flat place, geometrically speaking.

The result? It's bad news for the small universe crowd. There's no evidence for repeating patterns in the sky. But they shouldn't despair yet. This doesn't mean the universe is necessarily much larger than what we see--it just means that, even if it closes back in on itself, it's nonetheless bigger than the presently-observable slice of the universe.

Unfortunately, the expansion of space is accelerating, thanks to dark energy dominating the universe. That means that with the outskirts of the visible universe galloping further away from us, we have now already seen almost as much of the universe as we'll ever see.

So, we may live in a funnily shaped finite universe... but we'll likely never be able to prove it.

--

Mark Wyman is a human-shaped cosmologist at the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics in Ontario, Canada.