It's not quite as "foundational" as our usual topics (well it's a "Copenhagen interpretation" of sorts), but with climate issues dominating the news thanks to the start of the Copenhagen summit, it seems like a good time to talk about reactions to nuclear power. Gareth Mitchell, presenter of the BBC's Digital Planet and lecturer at Imperial College London, recently visited India to investigate local views on the controversial Madras Atomic Power Station near Chennai for the BBC World Service's Climate Connection series. Here's his account of recording the program.

From Gareth Mitchell:

The first sign of trouble was a heated exchange that suddenly blew up between an armed security guard and our driver Antony. Though the raised voices were in Tamil, it was clear that the guard was deeply unhappy, pointing angrily to my camera and recording equipment.

We were at the entrance to Kalpakkam, a small township that serves the nearby Madras Atomic Power Station. We had interviewed the plant's chief superintendent for our edition of The Climate Connection season on the BBC, exploring how India can meet its sharply increasing demand for electricity whilst keeping its carbon emissions in check.

After the interview, we'd wandered into the township to speak to the residents. We expected them to be lauding the employment and economic benefits of having a large power station on their doorstep and crowing about this reliable source of electricity, a luxury unavailable to many who live in India's rural communities.

Instead, we heard that the power actually bypasses the township in favor of the 8 million inhabitants of Chennai about 70km north. They told us that the power station forbids other businesses locating within the area, thereby curbing job opportunities.

Most seriously, the villagers claimed that power station workers had become ill, with several dying of cancer and that some the township's children were sick and lethargic. How can you be sure? I asked, anything could be making them ill, you can't be certain it's the power station. But, they pressed on, repeating their claims that the plant was a source of harm and hardship rather than wealth and opportunity.

The guard threatened to report us to the authorities and was making noises about us being detained until Antony worked some kind of magic and the man let it go. But the villagers' revelations were safely recorded and I had a stash of photos. Right now, it was definitely time to go.

[youtube: kbLSM2hFL7Q, 560, 340]

However attitudes to the power station are different in the city.

The ever-resourceful Antony drove us to a neighborhood of workshops and small business units in Chennai where he knew twin brothers who run a successful firm manufacturing and exporting cashew nut processing machines. The city's creaking electricity supply only provides 70 per cent of the power they need to run their heavy machinery.

Annoying though that seems, the brothers are quite sanguine. Out in the countryside, full power is only available for five hours a day. At least their supply is relatively stable, even if it is a lower fat version of what they'd ideally like.

And, for them, the Kalpakkam nuclear power station is a good thing. It's not, by a long way, the sole source of their electricity but the brothers are glad it's there and they're hoping for more nuclear plants in the future. They dismiss any suggestion that nuclear is a source of health problems. Anything that props up the power supply will be good for business.

Earlier we had interviewed Dr Pugazhendi--a firebrand of a man who has examined many Kalpakkam residents. Talking at us for forty minutes without pausing for breath, Dr Pugazhendi listed cases of cancer and other illnesses associated with the nuclear power station, insisting that he has solid evidence but that he has been blocked from carrying out full studies and publishing the findings.

The fact remains that there is no hard, published evidence that the nuclear plant has caused any illness among the local population. The station's management told us that they take their workers' health very seriously, regularly monitoring their wellness.

One of the villagers we met in Kalpakkam had given us Dr Pugazhendi's mobile phone number and when I called him, he jumped at the chance of talking to us. He'd drop everything, he said, and come and find us wherever we were.

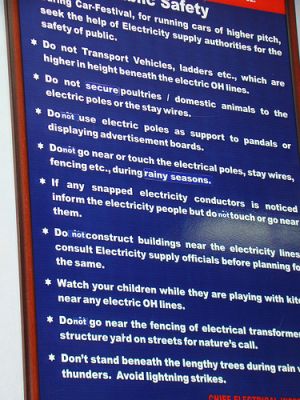

Whilst he was on his way, we turned up unannounced at the HQ of the Tamil Nadu State Electricity Board. (On the right is a photo of sign in the waiting room.) A contact in town had recommended we speak to the board's chairman, Mr C P Singh.

Sure enough, Mr Singh, an affable gentleman in an office overlooking the sprawling monsoon soaked metropolis granted us an interview. The most penetrating questions came from my companion Hita Unnikrishnan, a feisty young 'Climate Champion' of the British Council of India. A recent life sciences graduate, she now lectures in Botany at Bangalore's Jyoti Nivas College. She was travelling with me, taking on the role as local protagonist in our program.

Mr Singh obligingly fielded Hita's onslaught of questions. We learned that Tamil Nadu was the first state in India to supply electricity to all households and that it is one of the most progressive in the country when it comes to green energy. Half its power comes from hydroelectric and wind.

But the board is struggling to keep up with Tamil Nadu's rapidly increasing demand. Whilst renewables are part of the solution, the state needs more power stations. For now, there will be more power cuts and the state will have to continue buying in expensive electricity from outside.

But I spent most of the interview in a state of considerable anxiety. Earlier, after negotiating with Mr Singh's assistant for permission to meet the boss, I had been awaiting the verdict in a holding room down the corridor, when Dr Pugazhendi called me, saying he was in the area. I let slip exactly where we were.

This, I feared, was a potentially catastrophic move. One assumes that a well-known and vocal local opponent of the state's nuclear power station would be less than welcome in the Electricity Board's offices.

Throughout the interview with the chairman I had unsettling visions of Dr Pugazhendi, barging his way in, pushing aides and assistants aside and insisting on speaking to the BBC.

In the event, we met Dr Pugazhendi later on in a car park down the road and our interview at the Electricity Board passed off without incident. This was good. I could have done without a second altercation with security officials in as many days.

You can hear the program, which includes more about other renewable energy options in India, at: www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p0053sqq

Or download it here (until Thurs Dec 10): http://www.bbc.co.uk/podcasts/series/oneplanet/

Video on YouTube: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kbLSM2hFL7Q

Photos on Flickr: http://www.flickr.com/photos/23404067@N06/sets/72157622927385208/